In our global world economy it’s estimated that some 90% of all goods are carried and transported by sea. In 2021, about 1.96 billion metric tons of cargo were shipped globally! There are of course different types of ships to carry various kinds of goods, each optimized for specific cargoes and trade routes. Here is an overview of some of the most common types of vessels at sea:

- Container Ships: They are responsible for transporting cargo in large containers; in terms of sizing there are 20-foot and 40-foot containers called TEU (twenty equivalent unit) and FEU (forty equivalent unit) respectively. Some of the largest ships in this category can haul ≈24,300+ TEU’s! The goods that are carried in this type of vessel containers are usually consumer goods and other manufactured products. On board these ships have slots for fitting the standardized containers, which are held together by twistlocks to ensure proper stowage.

- Bulk Carriers: They transport unpackaged bulk cargo in large cargo holds which are watertight, ventilated spaces that contain the dry bulk. Some of the smaller sized ships can carry between 22,000 to 48,000 DWT (deadweight tonnage, a measure of how many tons of weight a ship can carry). The medium sized ships can carry 50,000 to 80,000 DWT while the largest of ships (called capesize vessels) can carry 120,000 to 200,000 DWT. The large ships can have up to 9 cargo holds, however the most common is usually around 5 to 7 holds. The type of cargo these ships carry are items like grains, coal, iron ore and other bulk materials. These cargo holds, where the cargo is stored, are sealed and covered by hatch covers which can roll out during loading and unloading. Some also have inbuilt cranes on board for easily loading and discharging cargo at the port.

- Tankers: They carry homogeneous cargo of gasses or liquids, such as fuel oils, edible oils, diesel/gas or petrol. Since these ships are not restricted by space constraints, they run on slow speeds around 15 knots (≈28 km/h). The smaller sized ships carry between 20,000 to 40,000 DWT, however the largest of ships can carry 400,000+ DWT. These ships are commonly used for long-haul crude transportation from different continents.

Now of course there are so many systems on a ship that all come together to make it function. However one integral system that every ship has is the engine room. In the heart of the ship there are many different types of machineries that are located all in one big room, aptly called the engine room. This key ‘room’ is located in the aft, bottom side of the ship as that is where the main propulsion of the ship, the propeller, is situated. The ER has 3 different stories, houses the ECR, and can get as hot as 50˚c while in operation.

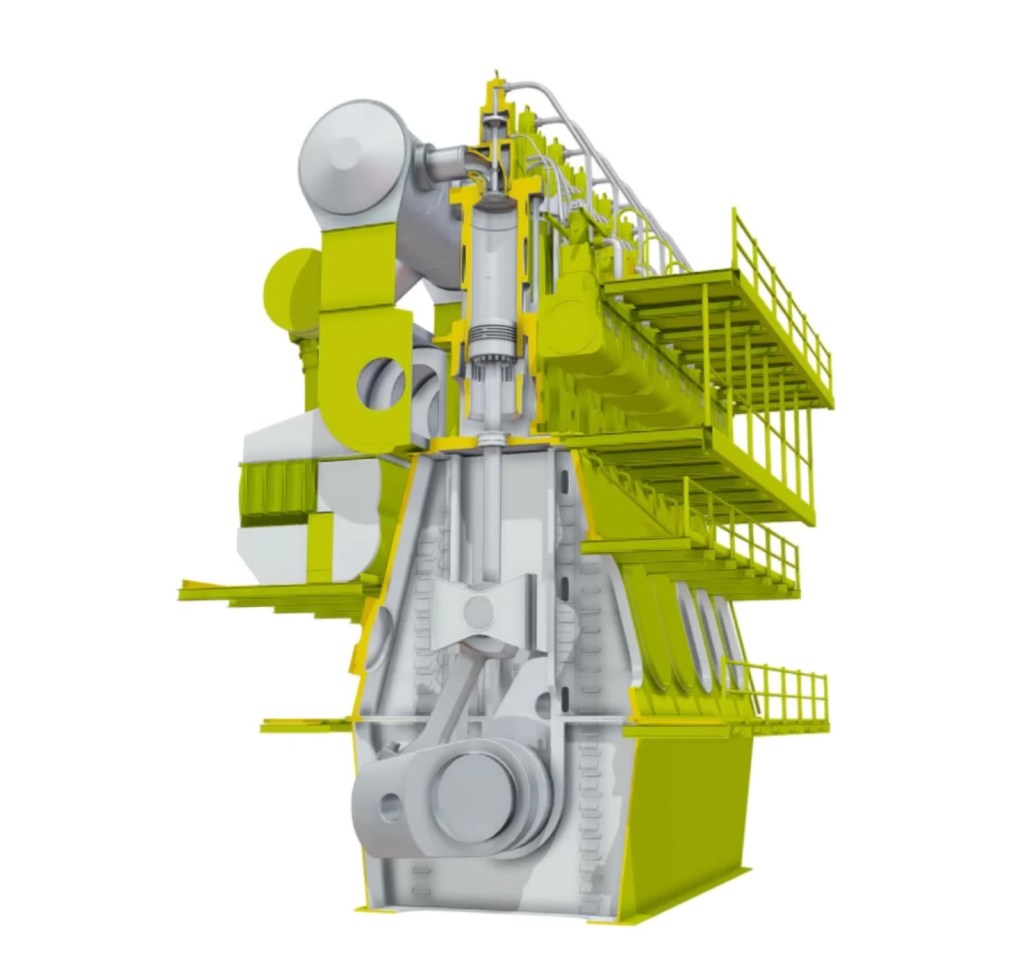

Let’s start with the main engine of a ship which is a 2-stroke engine having anywhere from 6 cylinders to a whopping 14 (as is the case for the largest of engines in the world)! The typical number however is around 6 to 9 cylinders. For most medium sized ships, 6 cylinders 2-stroke engines are used. Most of the engines run on what is called HFO (Heavy Fuel Oil) which is one of the dirtiest diesel based fuels, as it is a major pollutant (more info on this is written in my other articles about the environmental impacts of shipping). Due to this, many newer engines are dual fueled, meaning they can run off both HFO as well as a more environmentally friendly alternative such as ammonia or LNG (Liquified Natural Gas). Of course pollution to the environment is a big motivator for ships to make the switch but another key motivator might also be the new rules and regulations that are being set in place. One such example, taking effect from 2024, is the new EU regulations where shipping companies will have to buy EU carbon permits to cover 40% of their total emissions on a voyage. This is subsequently rising to 70% in 2025 and a full 100% in 2026. These new regulations encourage, and almost make it mandatory, for shipping companies to adapt to these rules set forth if they want to be profitable, which is the primary objective.

Now going back to our M/E (Main Engine), a typical one (6 cylinder 2-stroke) on a ship can produce ≈9400+ kW of power, [The power is dependent on the rpm (Revolutions Per Minute) of the flywheel]. At the top of the engine is where the cylinders are located, they have smooth finished cylinder liners fitted within where the whole liner movement of the piston takes place. A liner is defined by its bore (the internal diameter of the cylinder) and its stroke (the total vertical distance the piston moves, from BDC to TDC). The stroke-bore ratio is the ratio between these values, a 4:1 ratio for example could indicate a stroke of 2400mm and bore of 600mm. Located Just above the top of the liners are fuel injectors (usually 3) and exhaust valves (1). The exhaust valve is controlled by hydraulic oil chambers, the hydraulic oil is pumped in the upper chamber to push the valve down and in the bottom chamber to push the valve back up. The valve also has a spinning spindle which is powered by the motion of the exhaust gasses which exit out, this helps ensure there is even wear along the valve combustion and seat face. The fuel oil, which comes out from the fuel injectors, is pre-heated up by the boiler steam and pressurized to well over 0.8 MPa. Inorder for combustion to take place there needs to be fuel (supplied by the fuel injectors), sufficient heat and also oxygen. This oxygen is supplied near the bottom of the cylinder through many large holes. Before this air goes to the cylinder for combustion it is first compressed by the turbocharger (which is itself powered by the velocity of the exhaust gasses) and also cooled down (by the intercooler) in order to increase its density and thus its oxygen content within a certain volume. After the combustion process that happens towards the top, pushing the pistons down, the exhaust gasses all collect in an exhaust manifold that then goes to the turbocharger which we mentioned before, as its purpose is to compress the incoming inlet air.

Some ships also have what is called an economiser, this system captures the heat of the exhaust gas and uses it to convert it to steam. This system connects with the auxiliary main boiler and uses its steam for various applications such as heating up the fuel oil, which we discussed previously, and also for providing hot water ect… Throughout the cylinder liners and components located further below, there is a constantly running supply of lube oil. This oil coats all of the internal surfaces which have any surface to surface contact, this ensures minimal energy loss due to friction as well as reduces wear on such parts. This lube oil is collected at the bottom, cleaned up and then again passed through the system. Its cleaning is important as small pieces of grit and impurities can be present after each run or cycle. These are all the key components in the top section on the entire engine construction.

We shall now move on the lower sections which are located a floor below. The piston, which does vertical motion from TDC to BDC, is connected to a piston rod which is further joined to the cross-head. This cross-head is fixed on by guide rails, this is to ensure that the piston does not move side to side as this could cause serious damage to the liners. The cross-head serves as a bridge between the prison rod and the connecting rod. The con rod is then connected to the main crankshaft by bearings, this is to again minimize friction. The crankshaft has many counterweights placed at specific locations to balance out the load from the piston. On the end that is near the stern of the ship, the crankshaft is fitted with the flywheel mounting flange that connects directly to the flywheel. The purpose of the flywheel is to smooth out the rotation of the shaft, as not all the pistons fire all at once, as well as to store moment of inertia due to the flywheel’s large mass and radius. In a ship there is no gearbox, the rpm of the flywheel is the same as the rpm of the propeller submerged in the water.

Out from the flywheel is usually an intermediate shaft then another propeller shaft, connected by a bearing. Now, towards the very aft bottom of the ship, the propeller shaft is connected to the propeller. This shaft passes through the stern tube which prevents leakage as on the other side of this wall would be deep under water. The propeller exerts a force on the water, accelerating it back, and then it exerts an equal and opposite force thus propelling the ship forward. These are all the key components of a ship’s main engine that provide primary propulsion. It’s important to note the importance of two systems in the main engine that were not mentioned. One is the cooling jacket fresh water that carries out all the heat produced from all the engine, and transfers it back into the seawater through a heat exchanger. Second is the turning gear that is connected to the crankshaft of the engine, its job is to slowly move the engine (at <1 rpm) to ensure the lube oil is evenly distributed and to prevent any deformation or warping of the engine’s crankshaft due to its weight. By slowly rotating the crankshaft, it helps to distribute the load evenly, preventing any stress contraction that could lead to structural damage over time.

Of course there are so many systems on a ship that all work in unison to keep it operating, even in the engine room there are many different key components that all work together. I hope this article gave you a glimpse into the engine’s operations and how a ship is propelled. Year-over-year new technologies are constantly being engineered, tested and refined in order to make incremental efficiencies and improvements with every new design. In the future there will be improvements to the hydrodynamic architecture of vessels, the cleanliness of fuels (in terms of NOx emissions) as well as efficiencies in the fuel consumption, all contributing to more economically efficient vessels out at sea.

Leave a comment